NOTE: I wrote this article for the CNCF TAG (previously SIG) Observability Whitepaper about Observability, so you will see some of this write up there.

The Whitepaper itself, is a fantastic initiative that aims for a complete overview and state-of-the-art of modern observability. Purely community-driven and for the community! When writing this, it’s still in progress, so if you want to help writing this up or reviewing or redacting, please join our calls and #tag-observability channel on the CNCF Slack.

Correlating Observability Signals

Undoubtedly observability space is complex. To know more about the state and behaviour of the software we run, we collect different data types, from different angles, with different intervals and pipelines. We use various tools, different storage and visualisation techniques. We typically try to simplify this view by categorising those types of data into “signals”, for example, the three observability pillars:

- Metrics: Aggregatable numeric representation of state over a period of time.

- Logs: Structured or/and human-readable details representing a discrete event.

- Traces: Bits of metadata that can be bound to the lifecycle of a single entity in the system (e.g. request or transaction).

We also talk about the data that does not fit into the above categories, which is starting to earn their own “signal” badge, for example:

- Continues Profiling: Code-level consumption numbers (memory used, CPU time spent) for various resources across different program functions over time.

The first question that can come to our mind is, why we would ever create so many types? Can’t we have just one, “catch-them-all” thing? The problem is we can’t, in the same way, we can’t have a single bicycle that works efficiently on both asphalt roads and off-roads. Each type of signal is highly specialised for its purpose. Metrics are centred around real-time, reliable and cheap monitoring, that supports the first response alerting - a foundation for the reliable system. We collect Log lines that give us more insight into smaller details about the running system for more context. At some point, the details form a request tree, so Distributed Tracing comes into play with its spans and cross-process context propagation. Sometimes we need to dive even deeper and we jump into** performance application profiles** to check what piece of code is inefficient and use the unexpected amount of resources.

As you might have noticed already, having just one signal is rarely enough for a full, convenient observability story. For example, it’s too expensive to put too many details into metrics (cardinality), and it’s too expensive to trace every possible operation reliably with near-real-time latency required for alerting. That is why we see many organisations aiming to install and leverage multiple signals for their observability story.

Achieving multi-signal observability

Multi-signal observability is doable, and many accomplished it. Still, when you take a step back and look at what one has to build to achieve this, you can find a few main challenges, missed opportunities or inefficiencies:

1. Different operational effort

Unless you are willing to spend money on SaaS solution, which will do some of the work for you, it’s hard these days to have one team managing all observability systems. It’s not uncommon to have a separate specialised team for installing, managing, and maintaining each observability signals, e.g. one for metrics system, one for logging stack, one for tracing. This is due to different design pattern, technologies, storage systems and installation methods each system requires. The fragmentation here is huge. This is what we aim to improve with open-source initiatives like OpenTelemetry for instrumenting and forwarding part and Obsevatorium for scalable multi-signal backends.

2. Duplication of effort

When we look at the payloads for each of the mentioned observability signals, there are visible overlaps. For example, let’s take a look at the immediate collection of the data about the target visible in Figure 1. We see that the context about “where the data is about” (called typically “target metadata”) will be the same for each of the signals. Yet because behind each of the signals, there is a standalone system, we tend to discover this information multiple times, often inconsistently, save this information in multiple places and (worse!) index and query it multiple times.

And it’s not only for target metadata. Many events produce multiple signals: increment metrics, trigger logline and start tracing span. This means that metadata and context related to this particular event are duplicated across the system. In the open-source, there are slowly attempts to mitigate this effect, e.g. Tempo project.

3. Integration between signals on ingestion level

Given the multi-signal pipeline, it’s often desired to supplement each system with additional data from another signal. Features like creating metrics from a particular collection of traces and log lines compatible with typical metric protocols (e.g. OpenMetrics/Prometheus) or similarly combining log lines into traces on the ingestion path. Initiatives like OpenTelemetry collector’s processor that produces RED metrics from trace spans and Loki capabilities to transform logs to metrics are some existing movements in this area.

4. Integration between signals on usage level

Similarly, on the “reading” level, it would be very useful to navigate quickly into another observability signal representing the same or related event. This is what we called the correlation of signals. Let’s focus on this opportunity in detail. What’s achievable right now?

Correlation of Signals

In order to link observability data together, let’s look at common (as mentioned before, sometimes duplicated) data attached to all signals.

Thanks to the continuous form of collecting all observability signals, every piece of data is scoped to some timestamp. This allows us to filter data for signals within a certain time window, sometimes up to milliseconds. On the different dimension, thanks to the situation presented in Figure 2, each of the observability signals is usually bound to a certain “target”. To identify the target, the target metadata has to be present, which in theory allows us to see metrics, profiles, traces and log lines from the certain target. To narrow it even further, it’s not uncommon to add extra metadata to all signals about the **code component **the observability data is gathered from, e.g. “factory”.

As we see in Figure 3, this alone is quite powerful because it allows us to navigate quickly from each of those signals by selecting items from each signal related to a certain process or code component and time. Some frontends like Grafana already allows creating such links and side views with this in mind.

But this is not the end. We sometimes have further details that are sometimes attached to tracing and logging. Particularly, distributed tracing gets its power from bounding all spans under a single trace ID. This information is carefully propagated from function to function, from process to process to link operations for the same user request. It’s not uncommon to share the same information in your log line related to a request, sometimes called a Request ID or Operation ID. With a simple trick of ensuring that those IDs between logging and tracing are exactly the same, we have a strong link between each other on such low-level scope. This allows us to easily navigate between log lines, trace spans and tags, bound to the individual request.

While such a level of correlation might be good enough for some use cases, we might be missing an important one: Large Scale! Processes in such large systems do not handle a few requests. They perform trillions of operations for vastly different purposes and effect. Even if we can get all log lines or traces from a single process, even for a single second, how do you find the request, operation or trace ID that is relevant to your goal from thousands of concurrent requests being processed at that time? Powerful logging languages (e.g LogQL) allow you to grep logs for details like log levels, error statuses, message, code file, etc. However, this requires you to understand the available fields, their format, and how it maps to the situation in the process.

Wouldn’t it be better if the alert for a high number of certain errors or high latency of some endpoint let you know all the request IDs that were affected? Such alert is probably based on metrics and such metric was incremented during some request flow, which most likely also produced log line or trace and had its request, operation or trace ID assigned, right?

This sounds great, but as we know, such aggregated data like metrics or some log line that combines the result from multiple requests are by design aggregated (surprise!). For cost and focus reasons, we cannot pass all (sometimes thousands) requests ID that is part of the aggregation. But there is a useful fact about those requests we can leverage. In the context of such aggregated metric or log line, all related requests are… somewhat equal! So there might be no need to keep all IDs. We can just attach one, representing an example case. This is what we call exemplar.

Exemplar: a typical or good example of something

As visible in Figure 5, we can use all links in the mix in a perfect observability system, which gives us smooth flexibility in how we inspect our system from multiple signal/viewpoints.

NOTE: In theory, we could have exemplars attached to profiles too, but given its specialisation and use cases (in-process performance debugging), it’s in practice rare we need to link to single request traces or log lines.

Practical applications

We talked about ways you can navigate between signal, but is it really useful? Let’s go through two basic examples, very briefly:

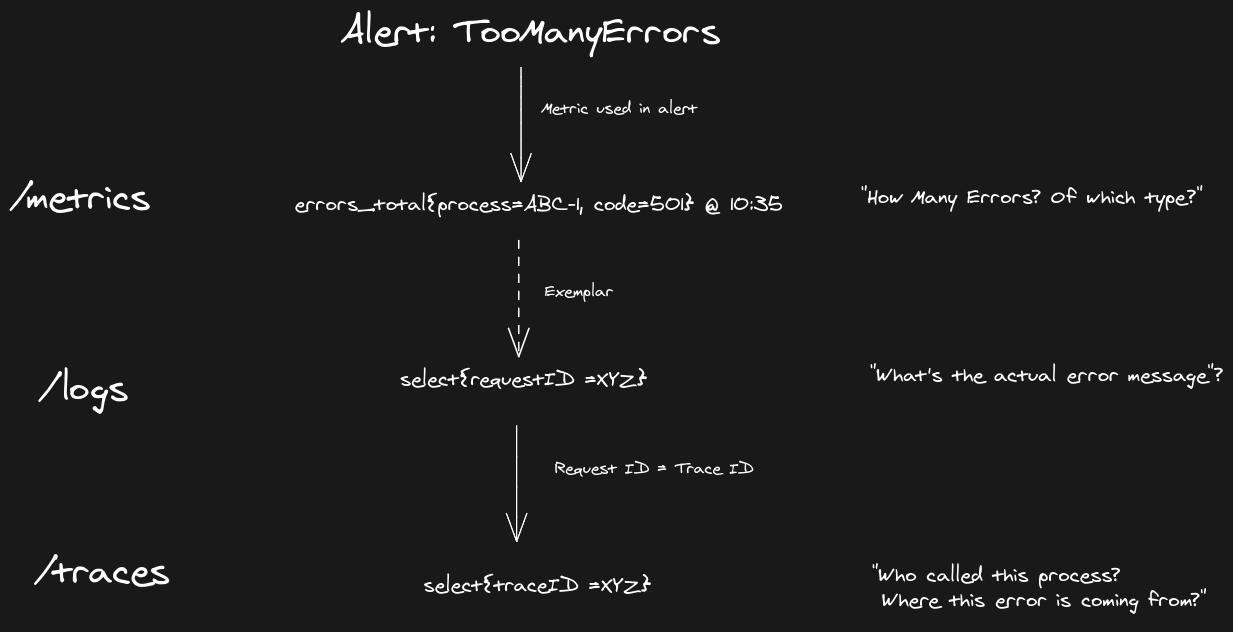

- We got an alert about an unexpectedly high error rate exceeding our SLO. Alert is based on a counter of errors, and we see a spike of requests resulting in 501 error. We take **exemplar to **navigate to the example log line to learn the exact human-friendly error message. It appears the error is coming from an internal microservice behind many hops, so we navigate to traces thanks to the existence of a request ID that is matching **trace ID. **Thanks to that, we know what exactly service/process is responsible for the problem and dig there more.

- We debug slow request. We manually triggered request with trace sampling and obtained trace ID. Thanks to tracing view, we can see among a few processes on the way of requests it was an ABC-1 request that is surprisingly slow for basic operations. Thanks to target metadata and time, we select relevant CPU usage metrics. We see high CPU usage, close to the machine limits, indicating CPU saturation. To learn why CPU is so heavily used (especially if it’s the only process in the container), we navigate to CPU profile using the same target metadata and time selection.

Practical Implementations

Is it achievable in practice? Yes, but in my experience, not many know how to build it. The fragmentation and vast amount of different vendors and projects fighting for this space might obfuscate the overview and hide some simple solutions. Fortunately, there is a big effort in open source communities to streamline and commoditise those approaches. Let’s look at some open-source ways of achieving such a smooth, multi-signal correlation setup. For simplicity, let’s assume you have chosen and defined some metrics, logging and tracing stack already (in practice, it’s common to skip logging or tracing for cost efficiency).

From the high-level point of view, we need to ensure three elements:

1. Consistent target metadata is attached to all signals

That might feel like a hard task already, but there is some shortcut we can make. This shortcut is called the pull model. For instance, consistent metadata is much easier in the Prometheus system (disclaimer: I am biased, I maintain Prometheus and derived systems), thanks to the single, centrally managed discovery service for target’s metrics collection. Among many other benefits, the pull model allows metric clients (e.g. your Go or Python application) to care only about its own metric metadata, totally ignoring the environment it is running in. On the contrary, this is quite difficult to maintain for push model systems, which spans over popular logging and tracing collection pipelines (e.g. Logstash, non-pulling OpenTelemetry receivers, non-tailing plugins for Fluentd, Fluentbit). Imagine one application defining the node it’s running on in key node and another mentioning this in label machine, another one putting this into instance tag.

In practice, we have a few choices:

- Suppose we stick to the push model (for some cases like batch jobs mandatory). In that case, we need to ensure that our client tracing, logging, and metrics implementations add correct and consistent target metadata. Standard code libraries across programming languages help, although it takes time (years!) to adopt those in practice by all 3rd party software we use (think about, e.g. Postgres). Yet, if you control your software, it’s not impossible. Service Meshes might help a bit for standard entry/exit observability but will disable any open box observability. The other way to achieve this is to use processing plugins that, e.g. OpenTelemetry, offers to rewrite metadata on the fly (sometimes called relabelling). Unfortunately, it can be brittle in practice and hard to maintain over time.

- The second option is to use and prefer a pull model and define the target metadata on the admin/operator side. We already do this in open source in Prometheus or Agent thanks to OpenMetrics for continuously scraping metrics and ConProf for doing the same for profiles. Similarly, there are already many solutions to tail your logs from standard output/error, e.g. Promtail or OpenTelemetry tailing collector. Unfortunately, I am not aware of any production implementation that offers tailing traces from some medium (yet).

BTW: I had this idea over a year to build a tail tracing solution but never got time for it. Would anyone like to experiment with this idea? Let me know, and we can join forces, collaborate!

EDIT(2021.05.09): Ben Ye pointed out cool PoC called “loki” (different to current logging project) made by Tom Wilkie at some point for tailing traces! Nice as starting point for something production grade!

2. Make Operation ID, Request ID or Trace ID the same thing and attach to the logging system

This part has to be ensured on the instrumentation level. Thanks to OpenTelemetry context propagation and APIs, we can do this pretty easily in our code by getting trace ID (ideally, only if the trace is sampled) and adding it to all log lines related to such a request. A very nice way to make it uniformly is to leverage middleware (HTTP) and interceptors (gRPC) coding paradigms. It’s worth noting that even if you don’t want to use a tracing system or your tracing sampling is very strict, it’s still useful to generate and propagate request ID in your logging. This allows correlating log lines for the single request together.

3. Exemplars

Exemplars are somewhat new in the open-source space, so let’s take a look at what is currently possible and how to adopt them. Adding exemplars to your logging system is pretty straightforward. We can add an exemplar in the form of a simple exemplar-request=traceID key-value label for log lines that aggregate multiple requests.

Adding exemplars for the metric system is another story. This might deserve a separate article I might write someday, but as you might imagine, we generally cannot add request or trace ID directly to the metric series metadata (e.g. Prometheus labels). This is because it would create another single-use, unique series with just one sample (causing unbounded “cardinality”). However, in open source, recently, we can use quite a novel pattern defined by OpenMetrics, called Exemplar. It’s additional information, attached to (any) series sample, outside of the main (highly indexed) labels. This is how it looks in the OpenMetrics text format scraped by, e.g. Prometheus:

# TYPE foo histogramfoo_bucket{le="0.01"} 0foo_bucket{le="0.1"} 8 # {} 0.054foo_bucket{le="1"} 11 # {trace_id="KOO5S4vxi0o"} 0.67foo_bucket{le="10"} 17 # {trace_id="oHg5SJYRHA0"} 9.8 1520879607.789foo_bucket{le="+Inf"} 17foo_count 17foo_sum 324789.3foo_created 1520430000.123

It’s worth mentioning that a metric exemplar can hold any information in the form of labels. Injecting TraceID is the most common designed use case, but it can be anything else too. Exemplar also can have a different value and timestamp than the sample itself. The process of passing such information in the Go looks pretty straight forward:

http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { now := time.Now() wd := &responseWriterDelegator{w: w} handler.ServeHTTP(wd, r) observer := requestDuration.WithLabelValues(strings.ToLower(r.Method), wd.Status()) // If we find a TraceID from OpenTelemetry we'll expose it as Exemplar. if spanCtx := trace.SpanContextFromContext(r.Context()); spanCtx.HasTraceID() && spanCtx.IsSampled() { traceID := prometheus.Labels{"traceID": spanCtx.TraceID().String()} observer.(prometheus.ExemplarObserver).ObserveWithExemplar(time.Since(now).Seconds(), traceID) return } observer.Observe(time.Since(now).Seconds()) return})

Once defined, they got scraped together with metric samples (make sure to enable OpenMetrics format in your instrumentation client) by OpenMetrics compatible scraper (e.g. Prometheus). When that’s done, you can query those exemplars by convenient Exemplars API defined by the Prometheus community:

curl -g 'http://localhost:9090/api/v1/query_exemplars?query=test_exemplar_metric_total&start=2020-09-14T15:22:25.479Z&end=020-09-14T15:23:25.479Z'{"status": "success","data": [{"seriesLabels": {"__name__": "test_exemplar_metric_total","instance": "localhost:8090","job": "prometheus","service": "bar"},"exemplars": [{"labels": {"traceID": "EpTxMJ40fUus7aGY"},"value": "6","timestamp": 1600096945.479,}]},(...)

Note that the query parameter is not for some magic ExemplarsQL language or something. This API expects any PromQL query that you might have used on your dashboard, alert or rule. The implementation is supposed to parse the query then and for all series that were used, will return all relevant exemplars for those series if present.

This API got adopted pretty quickly by Grafana, where you can, even now, on the newest version of AGPLv3 licensed Grafana to render exemplars and allow a quick link to the trace view. You can see the whole setup during our demo we did with Anaïs on this PromCon 2021 (video soon! For now available in Katacoda and GitHub here).

Of course, that’s just basics. There is whole infrastructure and logic in Prometheus done at the beginning of 2021 to support exemplars on scraping, storing, querying it and even replicating those in a remote write. Thanos started to support exemplars, so the Grafana.

It’s also worth mentioning that OpenTelemetry also inherited some form of exemplars from OpenCensus. Those are very similar to OpenMetrics one, just only attachable to histogram buckets. Yet, I am not aware of anyone using or relying on this part of Otel metric protocol anywhere, including relevant implementations like Go. This means that if you want to have a stable correlation, we already working ecosystem, OpenMetrics might be the way forward. Plus, OpenTelemetry slowly adopts OpenMetrics too.

Challenges

Hopefully, the above write up explains well how to think about observability correlation, what it means and what is achievable right now. Yet let’s quickly enumerate the pitfalls of today’s multi-signal observability linking:

Inconsistent metadata

As mentioned previously, even slight inconsistency across labels might be annoying to deal with when used. Relabelling techniques or defaulting to a pull model can help.

Lack of request ID or different ID to the Tracing ID in the logging signal

As mentioned previously, this can be solved on the instrumentation side, which is sometimes hard to control. Middleware and service meshes can help too.

Tricky tracing sampling cases

Collecting all traces and spans for all your requests can be extremely expensive. That’s why the project defines different sampling techniques allowing only “sample” (so collect) those traces that might be useful later on. It’s non-trivial to say which ones are important, so complex sampling emerged. The main problem is to make sure correlation points like exemplars or direct trace ID in the logging system points to the sampled trace. It would be a poor user experience if our frontend systems would expose exemplar of the link that is a dead-end (no trace available in the storage).

While this experience can be improved on the UI side (e.g., checking upfront if trace exists before rendering exemplar), it’s not trivial and presents further complexity to the system. Ideally, we can check if trace was sampled before injecting exemplar to logging on the metric system. If upfront sampling method was used, OpenTelemetry coding APIs allow getting sampling information via, e.g. IsSampled method. The problem appears if we talk about tail-based sampling or further processes that might analyse which trace is interesting or not. We are yet to see some better ideas to improve this small but annoying problem. If you have a 100% sampling or upfront sampling decision (ratio of request or user-chosen), this problem disappears.

Exemplars are new in the ecosystem

Especially Prometheus user experience is great because having Prometheus/OpenMetrics exposition in your application is the standard. Software around the world uses this simple mechanism to add plentiful useful metrics. Because Prometheus exemplars are new, so are OpenTelemetry tracing libraries, it will take time for people to start “instrumenting their instrumentation” with exemplars.

But! You can start from your own case by adding Prometheus exemplars support to your application. This correlation pattern is becoming a new standard (e.g. instrumented in Thanos), so help yourself and your users by adding them up and allow easy linking between tracing and metrics.

Higher-level metric aggregations, downsampling

Something that yet to is added is the ability to add exemplars for recording rules and alerts that might aggregate further metrics with exemplars attached. This has been proposed, but the work has to be yet done. Similarly, the downsampling techniques that we discuss for further iterations of Prometheus have to think about downsampling exemplars.

Native Correlation support in UIs

Grafana is pioneering in multi-signal links, but many other UIs would use better correlation support given the ways shared in this article. Before the Grafana, the space was pretty fragmented (each signal usually have its own view, rarely thinking about other signals). Prometheus UI is no different. Extra support for linking to other signals or rendering exemplars are to be added there too.

Summary

To sum up, there are many benefits of the consistent and unified multi-signal observability story. In some way, this is tripling the investment in good observability tooling, as you can get much more from your existing stack.

Based on my team on-call experience at Red Hat and before, the ability to navigate between all signals is a true superpower. We can already achieve a lot with the common target and component metadata, scoping by the time and leveraging single request ID. But undoubtedly, with the exemplars on top the inspection, debugging, and analysis journeys are much more efficient and user friendly. Please make sure you leverage this, add relevant feature request to project that needs some work towards this and.. Instrument your exemplars!

Stay Safe! 🤗

Comments